Postmortem: Every Frame a Painting

Every Frame a Painting is officially dead. Nothing sinister; we just decided to end it, rather than keep on making stuff.

The existing videos will, of course, remain online. But there won’t be any new ones.

The following is the script for what was supposed to be the final episode, voiced by both Taylor and myself. We were never able to make it. But we think it may be useful to some of you making your own work on the Internet, so we’re publishing it here.

OPENING WORDS

(TONY) Hi, my name is Tony… (TAYLOR) and my name is Taylor… and this is the postmortem for Every Frame a Painting.

(TONY) As many of you have guessed, the channel more or less ended in September 2016 with the release of the “Marvel Symphonic Universe” video. For the last year, Taylor and I have tinkered behind-the-scenes to see if there was anything else we wanted to do with this YouTube channel.

(TAYLOR) But in the past year, we’ve both started new jobs and taken on other freelance work. Things started piling up and it took all our energy to get through the work we’d agreed to do.

When we started this YouTube project, we gave ourselves one simple rule: if we ever stopped enjoying the videos, we’d also stop making them. And one day, we woke up and felt it was time.

A CORRECTION, FOR THE RECORD

(TONY) “Every Frame a Painting” was not the product of a single person, but of two people working, thinking, and disagreeing with each other.

This crediting issue was my fault. I finished the very first video with the words “Edited & Narrated by Tony Zhou” and ever since then, it has been hard to get people to notice that it now says “Written & Edited by Taylor Ramos and Tony Zhou.”

So just to make it clear: these videos were made by the both of us.

PART I: ORIGINS

(TONY) Every Frame a Painting started because of two things. The first happened in March of 2013. The second happened in April of 2014.

The first reason was that Taylor and I were dealing with the same problem: at work, we had to discuss visual ideas with non-visual people. I’m an editor, she’s an animator, but the problems we encountered were largely the same.

If you’ve ever tried to talk about visual ideas with non-visual people, you know how difficult it is. Many people can’t understand something until you show it AND explain it to them. Eventually I would just go to a computer, pull up a YouTube clip, sit next to them and point out specific things (this is how the Spielberg oner video started).

One day I thought: “I wish someone would make video essays this way — like someone sitting next to you, demonstrating visual literacy.” And that was how the idea of Every Frame a Painting was born.

But once I had the idea, I didn’t make it. All I did was talk about it for a year.

Instead, I would go to work, be frustrated by my boss, then come home angry. By this time, Taylor and I had moved to San Francisco, and while I went into the office every day, she worked from home. Some days, I was the only human contact she had. And for weeks and weeks and weeks, all she heard was my anger.

I came in one Tuesday and started spouting off about my boss. She turned around and cut me off. She said that I should stop complaining about other people, and instead spend my energy on more productive things. Maybe I should make those videos I keep talking about, instead of bitching about work, or else I’d wake up in ten years and realize I’d gotten nowhere. Then she closed the door.

Everything she said was true. Harsh, but true.

So naturally, I got mad at her. I stomped into the living room, turned on my computer, and — partly out of inspiration, partly out of spite — I started typing the first words: “Hi my name is Tony and this is Every Frame a Painting.”

And that was the second reason the channel began.

PART II: PROBLEMS AND SOLUTIONS

(TAYLOR) It’s tempting to look back on decisions we made three years ago and say that we knew which choices would eventually become important. But the truth is we made all those initial decisions based on instinct, and they ended up just working out.

Choosing form over content

The first choice Tony made was to focus on film form, rather than content. At the time, most YouTube videos seemed to focus on story and character, so we went in the opposite direction.

This made the videos really straightforward and more of a learning tool than anything else. Instead of showing a clip and talking about the plot, we were showing the clip and talking about the clip. A person could watch almost anything we made without having seen the films.

In fact, the videos often played better if you didn’t know what the films were. That way, all you could do was react to the interplay of images and sound.

Making a cohesive channel

The second choice was mine. After watching the first video, I argued that Tony should make a channel instead of individual videos.

Making it a channel meant creating a uniform tone and style, something that Tony initially resisted. But I argued that a person who watched one video would be more likely to come back and watch another if there was a uniform style — even if they weren’t interested in that specific topic.

This meant we could get away with talking about less-known subjects and plenty of people would still watch because the format was the same. To his credit, Tony now admits I was right. (Tony’s note: “I refuse to admit this”).

Creating a style from our biggest restriction

In order to make video essays on the Internet, we had to learn the basics of copyright law. In America, there’s a provision called fair use; if you meet four criteria, you can argue in court that you made reasonable use of copyrighted material.

But as always, there’s a difference between what the law says and how the law is implemented. You could make a video that meets the criteria for fair use, but YouTube could still take it down because of their internal system (Copyright ID) which analyzes and detects copyrighted material.

So I learned to edit my way around that system.

Nearly every stylistic decision you see about the channel — the length of the clips, the number of examples, which studios’ films we chose, the way narration and clip audio weave together, the reordering and flipping of shots, the remixing of 5.1 audio, the rhythm and pacing of the overall video — all of that was reverse-engineered from YouTube’s Copyright ID.

I spent about a week doing brute force trial-and-error. I would privately upload several different essay clips, then see which got flagged and which didn’t. This gave me a rough idea what the system could detect, and I edited the videos to avoid those potholes.

So something that was designed to restrict us ended up becoming our style.

The limits of our choices

And yet there were major problems with all of these decisions. We wouldn’t realize it until years later. But by creating such a simple, approachable style that skirted the edge of legality, we pretty much cut ourselves off from our most ambitious topics.

For instance, we’d always wanted to talk about Tarkovsky, but it’s impossible to talk about how he moved the camera without talking about why he moved the camera — and that meant playing very long shots (impossible due to Copyright ID) and discussing religion.

Similarly, we could never figure out how to tackle Agnes Varda, because our favorite idea required shooting new footage that didn’t mesh well with what existed.

The script you’re reading right now is the ultimate example of our failure. We could not figure out how to turn this script into a video essay. Half of the things in this script required filming new footage, or using still images or extensive re-writes to fit other people’s footage. In other words, this script shows the limits of the style we forged three years ago — and frankly, it was pretty constricting.

PART III: GOOD HABITS

Here are some habits we picked up while making essays. Take whichever you like, ignore the rest.

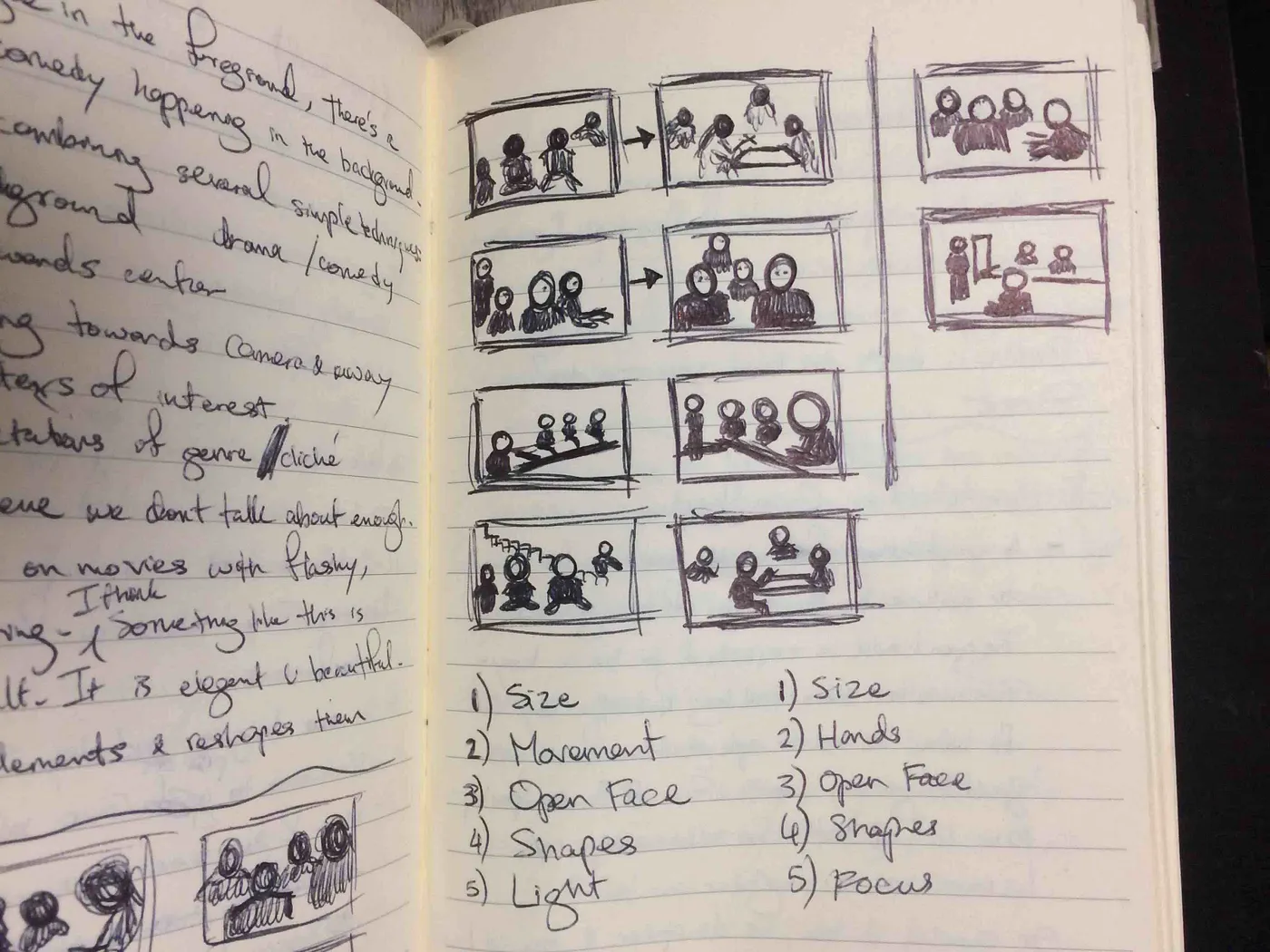

Keep a notebook

Whenever you have an idea, jot it down (along with the date), then forget about it.

The most important part of the process is to forget. Every idea seems amazing at the moment of inception, but once you sleep on it and check the notebook weeks later, you’ll find that your brain has already forgotten the weak ideas, but still thinks about the promising ones.

Every idea we’ve ever had for a video started in one of these notebooks, and many of them gestated for months. A few of them were written down in 2011, three years before the channel even began.

The end result is that you (the audience) are only seeing the stuff that passed through our first filter: are we still thinking about this idea long after we first came up with it?

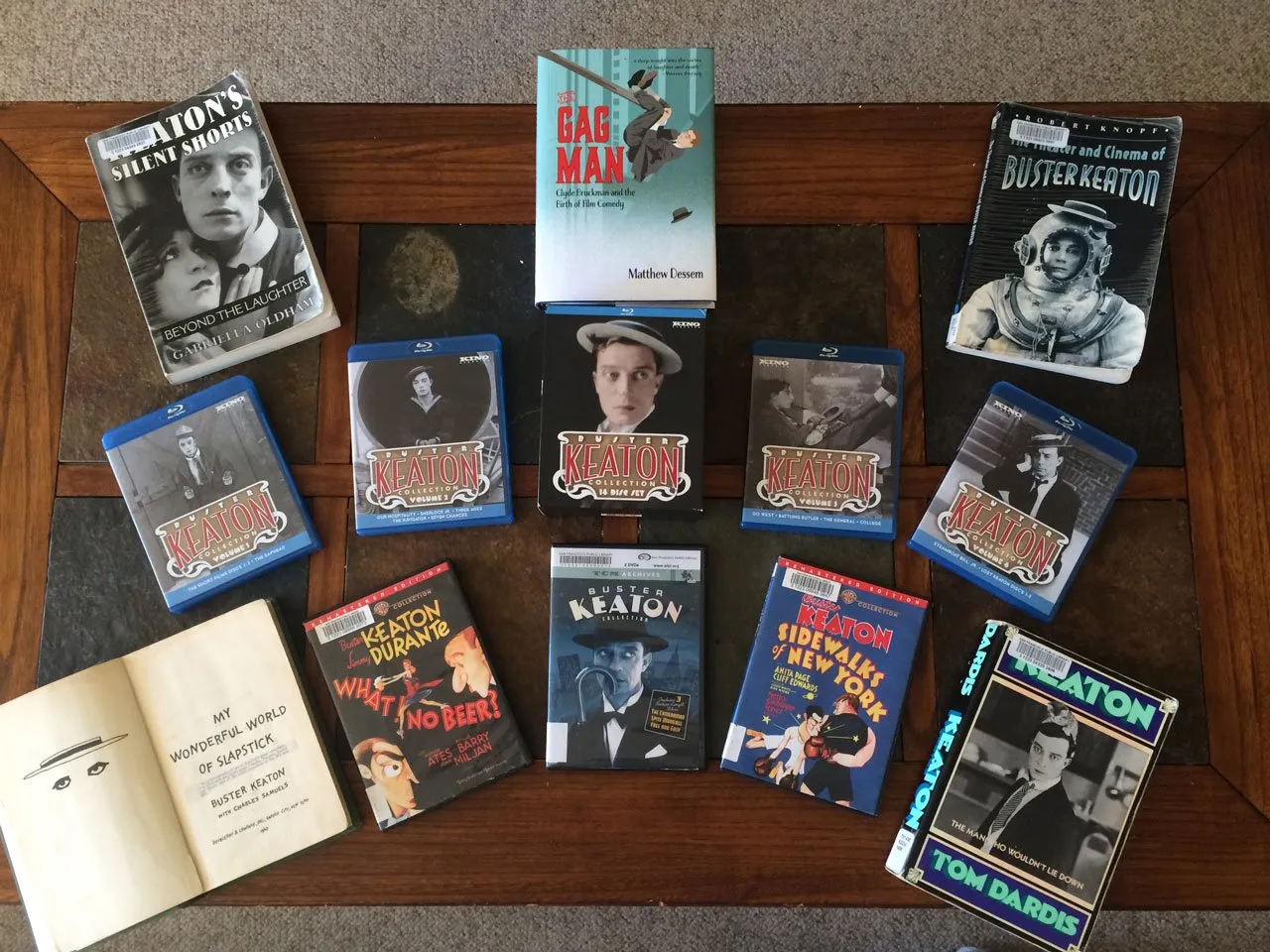

Research offline

A huge percentage of the Internet is the same information, repeated over and over again. This is especially apparent on film websites; they call it aggregation but it’s really just a nicer way to say regurgitation.

So go to the library. Read books. We cannot emphasize this enough: read books, read books, read books. Your work is only as good as your research, and the best research tool we have is the public library (or a film archive/research library if you’re lucky).

It’s very tempting to use Google because it’s so quick and it’s right there, but that’s exactly why you shouldn’t go straight to it. By taking your research to the library, you’re immediately breaking out of the online cycle of repetition, and your work will improve immediately.

Test ideas out loud

We like to turn each essay’s premise into a very simple statement or question: Can you hum any musical theme from a Marvel film? How do you show a text message in a movie?

Then we take that simple question and we test it out on real people — usually our friends (who are also filmmakers), usually over drinks or dinner. The key is to ask the question casually, as if we aren’t planning to make an essay.

The goal is to see if people react to an idea without us trying to sell it. Because if the basic idea is already interesting to people, it’ll only get better once we sharpen and hone it into a proper argument. But if nobody bites at the early stage, that usually means the idea needs more time to develop, or maybe we’re asking the wrong question.

Focus on the fundamentals

Jerry Seinfeld has a quote we really like. He was talking about joke writing and he said:

“…you can put all kinds of furniture in, but you gotta have steel in the walls.”

He meant that a comic can dress up their act with whatever gimmick they want, but underneath it all, there still has to be a joke.

We feel the same way about video essays. You can put whatever window dressing you want: you can play a creepy serial killer, you can have nice motion graphics, you can even throw Nujabes on the soundtrack. But you’re still making an essay, which means it’s gotta have an argument.

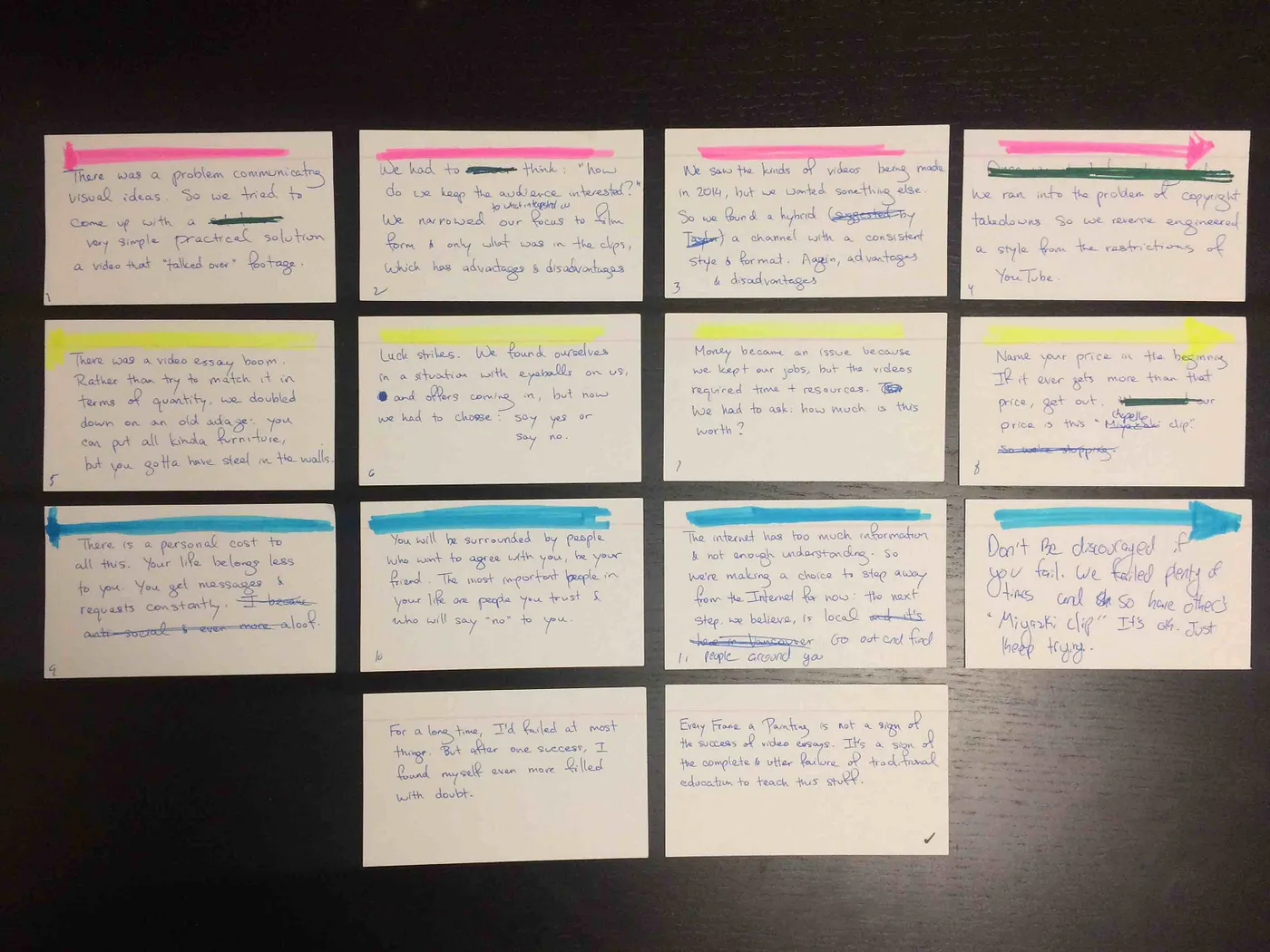

Tony and I do something quite old-fashioned. We write all of our points down on flash cards and then put them on a table. Then we rewrite, re-arrange, and try them out in a number of different combinations until we figure out the tightest, strongest through-line for the argument.

Once we find this spine, Tony has to memorize all the flash cards in order. He has to be able to say the entire argument, beginning to end, without stopping. If he screws up, I make him go back to the beginning and do it all over again.

Flash cards may or may not work for you, but we encourage you to take Seinfeld’s advice: put steel in the walls.

Keep your shit organized

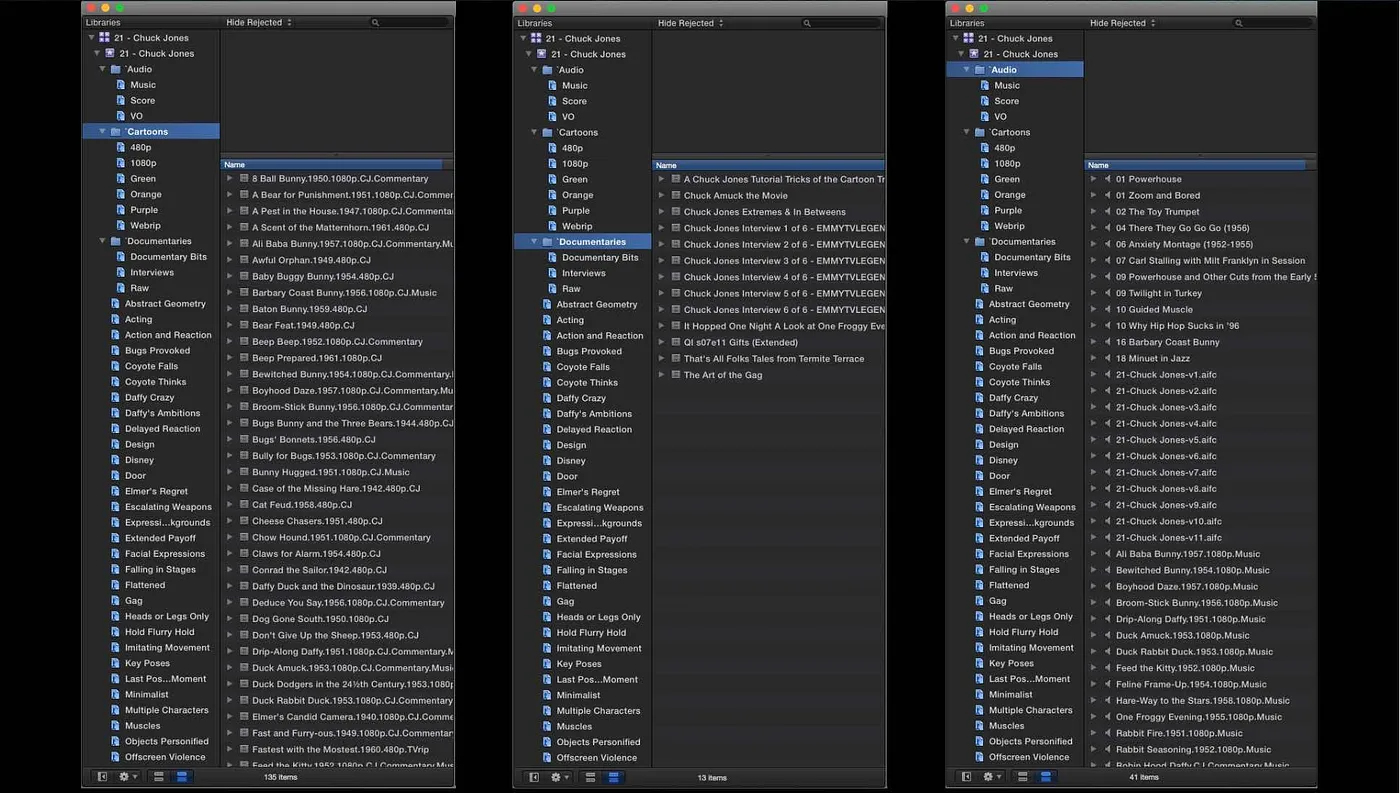

Many people falsely believe that I have some sort of crazy memory for clips and movies. Not really. I just keep everything organized. I’m an editor; this was beaten into me.

For “Vancouver Never Plays Itself” we used footage from 85 different films, but there were actually over 200 films in the project file. Keeping everything organized and annotated was the only way I could find anything.

Every Frame a Painting was edited entirely in Final Cut Pro X for one reason: keywords.

The first time I watch something, I watch it with a notebook. The second time I watch it, I use FCPX and keyword anything that interests me.

Keywords group everything in a really simple, visual way. This is how I figured out to cut from West Side Story to Transformers. From Godzilla to I, Robot. From Jackie Chan to Marvel films. On my screen, all of these clips are side-by-side because they share the same keyword.

Organization is not just some anal-retentive habit; it is literally the best way to make connections that would not happen otherwise.

PART IV: UNACKNOWLEDGED TRUTHS

We feel there are a lot of misconceptions or ideas that people believe about making stuff on the Internet. Here’s the truth, as we see it.

Work with a partner

There’s a common myth in the arts — the lone genius, usually a man, creating everything by himself. For the most part, neither of us has found it to be completely true. Look up most cases of a lone genius, and you’ll find a footnote about some unacknowledged helper.

Here’s how we work: Tony usually researches, writes and edits alone. But I do everything else: I edit every draft, watch every version, watch all the clips, do the flash cards, and build the thesis. I am the first and last audience that sees everything before it goes out. And the closest description we’ve ever come up with is that he is the editor, and I am the editor’s editor.

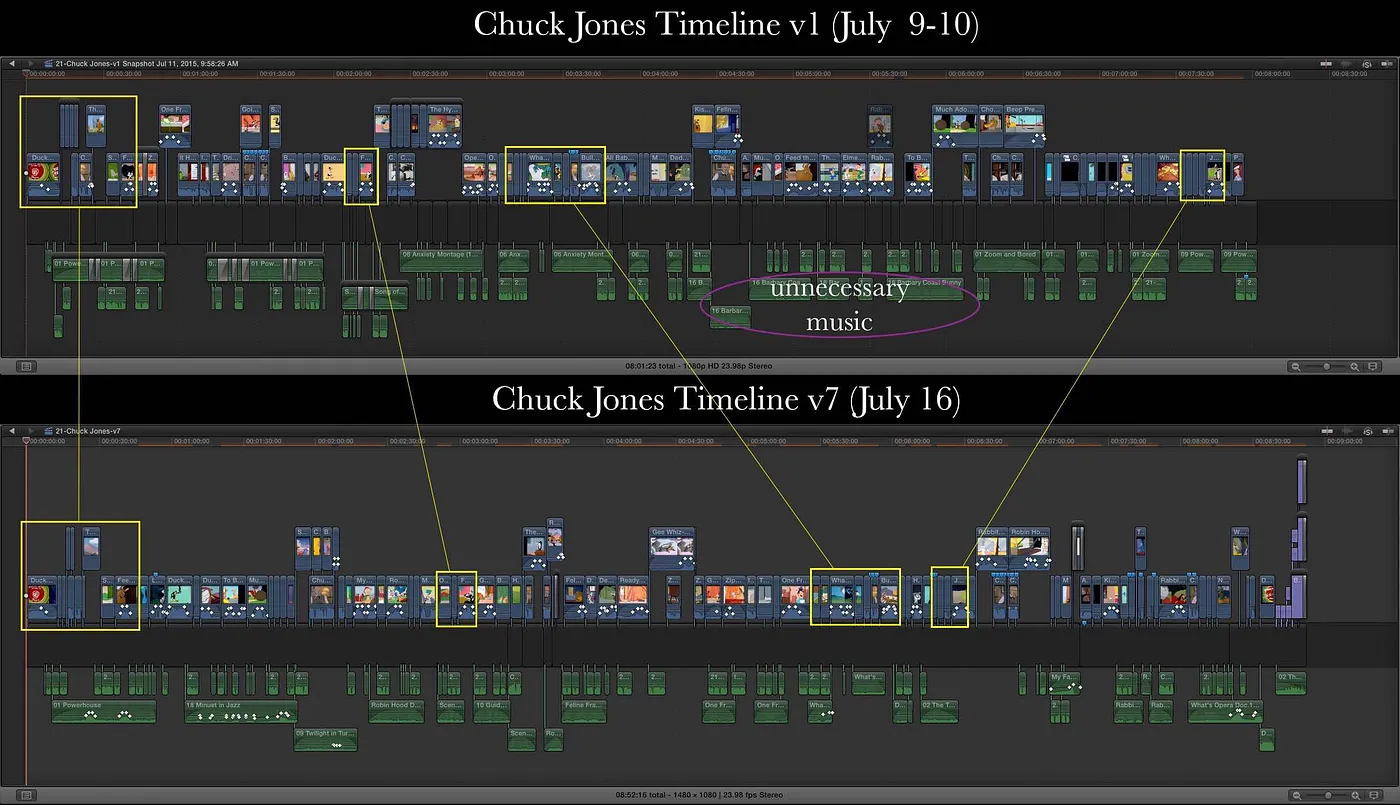

If you look at the picture below, you’ll see Tony edited version 1 of the Chuck Jones video by himself. Then we worked together for 7 days to create version 7 (the final). The yellow boxes are the only parts that stayed the same, and even those sections got moved around.

But most of all throughout this process, I’m a sounding board. Tony and I often build a thesis by arguing the points with each other. Except for a handful of videos, that has basically been our process for three years. We’re not saying that this system will work for everyone, but having two sets of eyes has worked really well for us.

There is no such thing as free content on the Internet

Everything costs something to make. If a person is putting out content for free, that means they’re not getting paid for their time.

Video essays cost money to make. There’s the cost of the research, the writing, the assembling of materials, the editing. It adds up to hours and hours of work for something that takes minutes to consume. My average just for editing (not anything else) is about 8 hours of editing for every 1 minute of video essay. So the 9-minute Jackie Chan video was around 72 hours of editing. It was probably at least double for research and writing.

With Patreon donations, Every Frame a Painting was eventually able to break even. But from April 2014 until December 2015, we were making video essays at a loss. We were never in danger of not making the rent, but it got pretty financially stressful on several occasions.

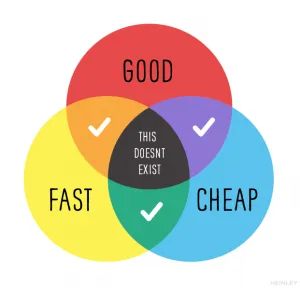

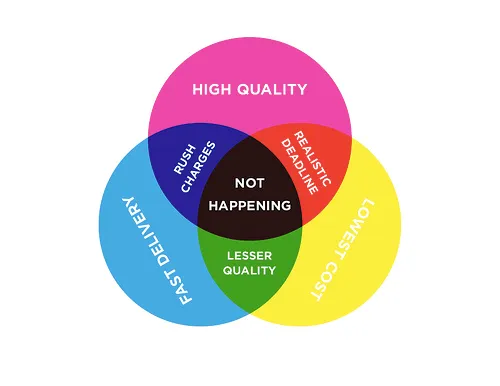

Nobody can cheat the triangle

Everyone who works in filmmaking knows the triangle: Faster, Cheaper, Better. Pick two. A film can be made fast and cheap, but it won’t be good. Or you can make it fast and good, but it won’t be cheap. Or it can be cheap and good, but it won’t happen fast.

Every Frame a Painting was made after we came home from our day jobs and paid our bills. That kept it cheap. We also tried really hard to make it good. Which ultimately meant we had to sacrifice “fast.”

The big danger for future video essayists is that large websites have started moving away from the written word and towards video, which is completely unsustainable. Video is just too expensive and time-consuming to make.

(TAYLOR) Unfortunately, no matter how hard you try, nobody can cheat this triangle. And sooner or later, all of these large sites will bleed money, at which point some executive will say “We need to make our content both faster AND cheaper!”

This is why we encourage every person who wants to make something on the Internet to understand the value of independence. This is not about artistic integrity or even money. We kept Every Frame a Painting independent because as long as we could control this triangle, we could control the end result.

We didn’t care about cheap or fast, we cared about it being good. If we found a company willing to pay for it to happen fast, we’d work fast (full disclosure: we eventually found two, Criterion and FilmStruck). If nobody was willing to pay, then we worked slow.

But if we sold the channel to another company, or partnered with some network, then we would no longer control the triangle. And guess which of these three things would get sacrificed first?

Know thyself and thy audience

Nothing really prepares you for the experience of suddenly having “an audience” on the Internet. The experience is different for every person, but I suspect the two major feelings are the same: there’s that initial dopamine rush of “Oh my God somebody likes me” followed by that creeping fear of “I better not fuck this up.”

George Orwell has this great quote:

What people always demand of a popular novelist is that he shall write the same book over and over again, forgetting that a man who would write the same book twice could not even write it once.

The Internet, and YouTube in particular, is a massive echo chamber of people asking you to write the same book over and over again. For your own sanity, you need to keep those voices at arm’s length. But because of that combination of dopamine and fear, it seems as though a lot of people end up leaning into what the audience wants.

We’re not asking you to ignore the audience completely; it’s more about setting clear boundaries between you and them.

My belief is that if you give the audience exactly what they ask for every time, they will probably enjoy it, but on some level they’ll lose respect for you. Hell, you’ll lose respect for yourself.

(TAYLOR) And I believe that there is a balance that can be found, but you and the audience should be equally as passionate about the idea. The key is nuance.

So with Every Frame a Painting, we made it clear that we would not accept requests; we came up with all the ideas and set up boundaries. Not everybody needs to set the same boundaries we did, but you need to have something.

Success can be scarier than failure

The idea of failure is always scary. Nobody wants to fail, especially not in front of other people. But this script you’re reading is a failure.

The reason we‘re putting it out there isn’t as an act of bravery or anything; we just wanted to be honest. Failure is a fact of life — certainly a fact of any life in the arts. It’s the only way we’ve ever learned anything.

(TONY) For us, Every Frame a Painting ended up being both a personal and a professional success. But over time, I felt trapped by what we’d created — and also trapped by that success.

Every time I mentioned some film, I’d hear, “are you gonna make a video about it?” Every time I started writing something, even for my own amusement, a voice in the back of my head would say “how do I make this accessible to my audience?” I stopped experimenting in my editing, mostly because it was too far outside the margins of what I was making on YouTube.

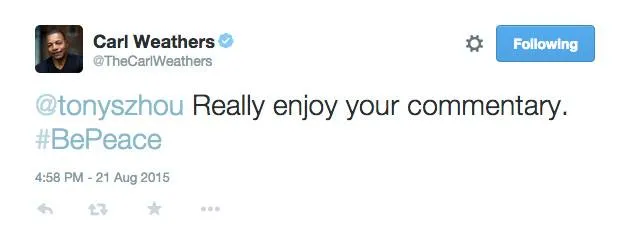

It wasn’t even fun making jokes on Twitter anymore, because they got taken at face value:

I’d been a working video editor since I was 19 years old. I’d spent three years of my personal time editing video essays. And now I could barely stand to look at my own work. Eventually, the solution became clear: go do something else.

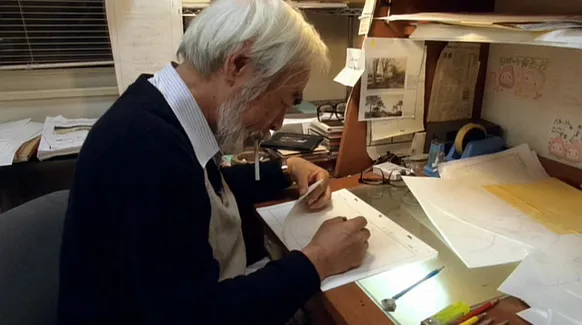

(TAYLOR) Whenever Tony got really down like this, I would remind him of a clip that we both love, from the Studio Ghibli documentary “The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness.” It’s a moment when Hayao Miyazaki is trying to draw a specific airplane. And for some reason, he cannot do it.

For days and days, he keeps trying to draw this plane, but nothing meets his satisfaction. Eventually, he realizes that he’s spent too much time on it. So he hands the plane off to another animator, and he moves on to something else.

For me and for Tony, this clip is extremely reassuring. If Miyazaki — the world’s greatest living animator — can admit defeat after trying his best, then it’s okay for everyone else. If he can let go, then so can we.

FINAL WORDS

Every Frame a Painting is over, because that period of our lives is over. We have no idea what’s next, but we can tell you that we’re enjoying the time we spend at our jobs, and the time we spend on other side projects that nobody knows about. It also doesn’t hurt that we’re now back home in Vancouver.

Thank you all for watching and supporting us over the past three years. We can never express what an amazing experience this has been and how much this has meant to us. We hope that this script may help someone somewhere. Just liked we hoped the videos would. Maybe we’ll see you for the next project. But for now:

My name is Tony and my name is Taylor, and this concludes Every Frame a Painting.